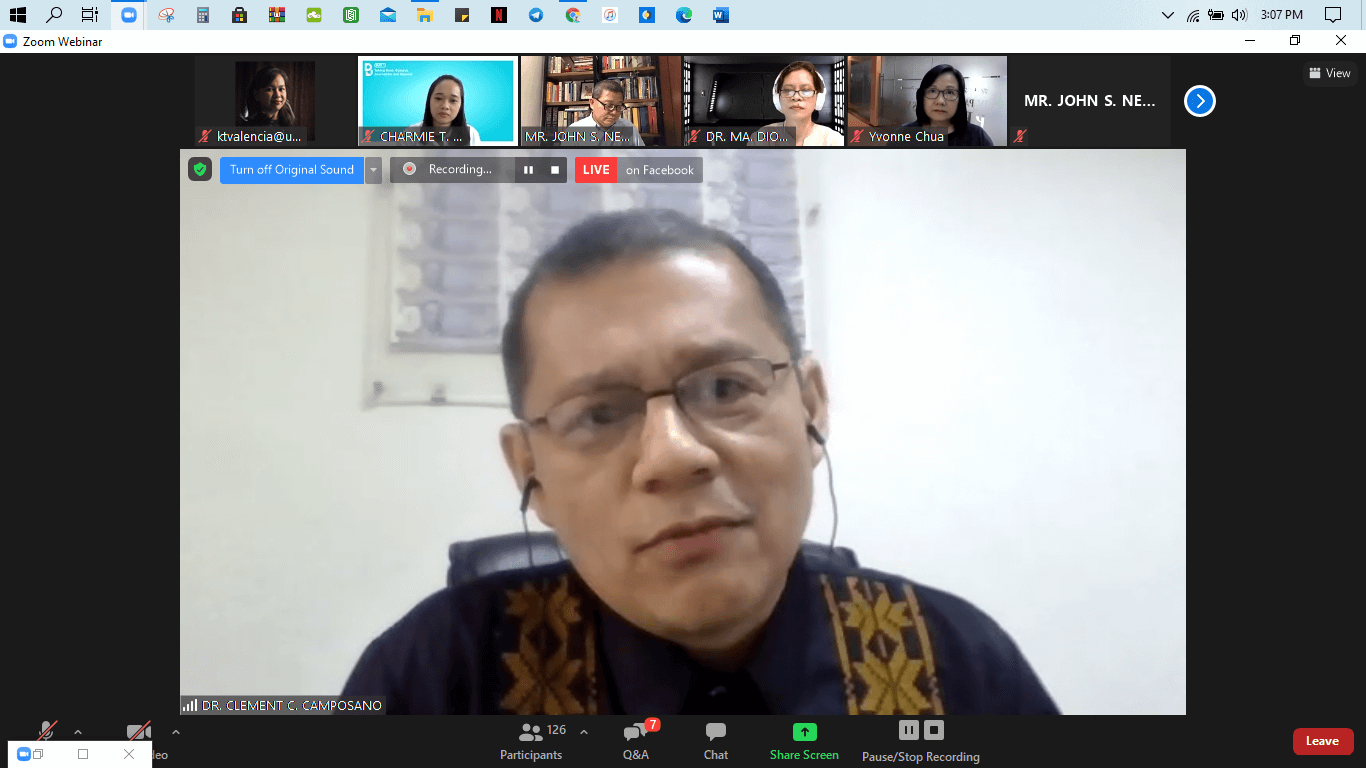

Transcript of Chancellor Clement Camposano’s presentation that was delivered last Monday, February 22, 2021 on Day 1 of 'The 3rd National Conference on Democracy and Disinformation' with theme: New Normal, New Media: Emerging Challenges of Disinformation in the Philippines.

Keeping our campuses free: Democracy, campus journalism, and social media

One of the issues I was asked to address for this roundtable is, “what is democracy and disinformation from the perspective of an academic institution?” Let me say at the outset that now is not the best time to be academic about this --- not when the University itself is under siege. Not physically as one might imagine, although this has happened in the past. The University is under siege because there is a campaign of vilification against it, a campaign intent on portraying our campuses not only as breeding grounds of radicalism (nothing wrong with it, if you ask me) but also as safe havens for enemies of the state.

Nonetheless, this is a teachable moment. A good opportunity for us to learn about democracy and disinformation. The first point I would like to make is that a large part of the struggle to keep democracy alive in this country --- in any country --- will be the struggle to keep our campuses free. Our democratic impulses are not part of our genetic inheritance. One is not born with them. These are learned; habits of mind we very likely imbibed when we were still students finding our way in the intellectual wilderness. To keep democracy from breathing its last, we need to keep our campuses alive. Alive with ideas, with disputations, with political dreams of all sorts. Alive with politics, broadly construed.

This is why the notion that the state needs to protect students from certain ideas is profoundly undemocratic. And dangerous. How does one learn to be democratic without practicing democracy? How does one learn to ride a bicycle without actually getting on top of one and risking a fall? Are some ideas dangerous? Well, most great ideas are dangerous! Leaving room for ideas that upend our received views of the world is the price we pay for keeping society free, especially from those who presume to think for us. Critical minds cannot be nurtured in the protective shadow of a paternalistic state.

A few examples will suffice: The notion of natural rights, on which many democratic constitutions are founded, was a terribly dangerous idea to a celebrated thinker like Edmund Burke. The brilliant political philosopher was convinced it threatened the institutions of society. The claim that women were the political equal of men was also dangerous not too long ago. So was the idea that a diverse group of Christianized Indios speaking different languages constituted a single nation. Thousands paid with their lives for dreaming that dream.

The other point I wish to make is that disinformation --- not third-rate, would be dictators --- is today a far more serious threat to the university, and by extension, to democracy. The volleys of disinformation, distortion, and fakery levelled at the University are threatening in two ways. First, they justify the work of those who would constrict the democratic space that our campuses signify, on behalf of the patriarchal presumption about the need to protect “children” from political exploitation (at a time when we need to stop treating young people as children!).

Second, and more seriously in my view, the current campaign of disinformation directed at the University works to distort and downgrade public understanding of the role universities play in society. Providing skills leading to gainful employment is not all that universities do. Universities exist primarily to ensure societies do not stagnate. Universities are purveyors of innovation in all spheres of life, from the technological to the political, to the sexual. Innovation requires daring, and daring is born of latitude and a restless spirit. Activism is good for society (there, I said it).

Where is campus journalism in all of this? Campus journalism can help galvanize resistance within the academic community and keep our campuses free from external interference. More importantly, by feeding the flames of intellectual controversy and helping create a climate of debate and intellectual contestation, campus journalism can help keep alive the restless spirit that makes universities what they are. We need campus journalists who are not only good at reporting what they think is going on. We need campus journalists who will be generous with their opinion and who will not shy away from hot-button issues.

Just as important, universities today need campus journalists who can grapple with the challenges and possibilities presented by social media, which has become the leading channel for news, information, and opinion. Let us stop thinking about the internet and its associated technologies simply as tools of communication. They are not. In fact, technology, in general, cannot simply be thought of as a means to an end. Digital technology has restructured human interaction, and this can have profound consequences for the way society works. As Daniel Miller (2005) said, “the things that people make, make people.”

Allow me to briefly discuss what I mean here. Steffen Dalsgaard (2008) argues that offline social life is fundamentally different from online sociality. Let us consider arguably the most popular social media site today: On Facebook, a person is always at the center of his own social universe, even as he must also see his “friends” as similarly situated --- i.e., as centers of their own social universes (9). Most interactions on Facebook are framed by an exchange relationship created when one user admits another into his or her network (McKay 2010). Facebook users sustain themselves mainly by receiving and giving affirmation.

This prompted sociologist Zygmunt Bauman (2016, Online) to bewail that what social media sites create are networks, not communities. “The difference between a community and a network is that you belong to a community, but a network belongs to you”, he points out. “[It’s] so easy to add or remove friends… that people fail to learn the real social skills, which you need when you go to the street when you go to your workplace, where you find lots of people who you need to enter into sensible interactions with”.

For Bauman, social media are not conducive to dialogue. He says that “…most people use social media not to unite, not to open their horizons wider, but on the contrary, to cut themselves a comfort zone where the only sounds they hear are the echoes of their own voice, where the only things they see are the reflections of their own face”. He ends by saying that, “[social] media are very useful, they provide pleasure, but they are a trap.”

This has implications for public discourse and also for citizenship and civic engagement. Will Facebook, in its present incarnation, enable us to comfortably move from our digitally mediated tribalism towards that larger society of anonymous others so essential to democracy? If a sense of this larger society is lacking in our politics today, can social media be used to remedy it? Can social media be used to create genuine democratic communities rather than tribal networks?

I remain hopeful, but it is important to accept that the current architecture of social media sites like Facebook works against civic engagement. Which is not to say it cannot occur, since indeed there are social media forums that facilitate discussion of public issues. We cannot also generalize too much across platforms: Facebook is restricted, but Twitter is more open. Facebook can also be many things to many people, and we need to pay attention to the specific ways it is appropriated by users. The internet is still in its infancy, and we have barely scratched the surface.

For social media to serve the ends of meaningful public discourse and citizenship, it needs to evolve, even as we need to evolve with it. Here, campus journalists can play a strategic role. It is not far-fetched to imagine these digital natives using their technical know-how to invent new forms of journalism. Additionally, I challenge our young campus journalists to also explore ways for social media to be harnessed to offline activities. Offline is where we bear the consequences of bad governance and the benefits of strong communities. Offline is where we live and where we are most likely to become good citizens.

This brings me right back to our physical campuses where civil sociality (Anderson 2011), where civic habits and dispositions can be imbibed and enacted. Indeed, where we learn to be public persons and resist the allures of modern tribalism. The challenges are very real, but so are the possibilities.